Smartskin: Replica of Human Skin Feels More Than the Real Thing

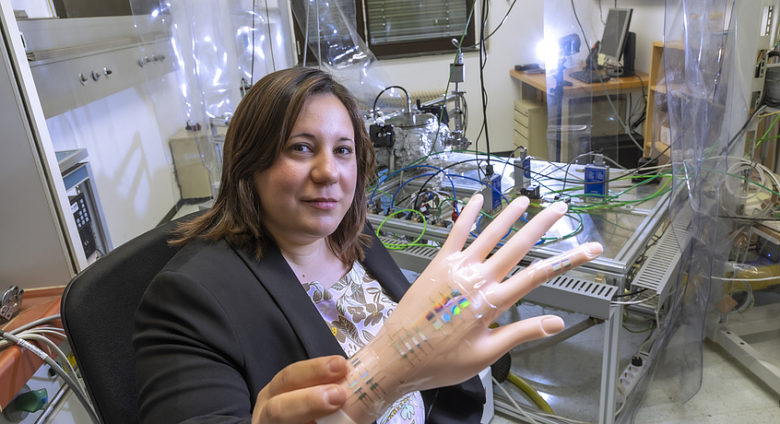

Ever wondered what the future of technology holds? Artificial intelligence, biofabricated organs, in-vitro food, and vegan meat? Well, there is more to it! Recently a major breakthrough brought scientists even closer to creating a replica of the human skin. Dr. Anna Maria Coclite, an Associate Professor at the Institute for Solid State Physics at TU Graz and formal postdoctoral researcher at MIT, and her colleagues have succeeded in developing a three-in-one hybrid material “Smartskin” for the next generation of artificial electronic skin. For her research and contribution, Dr. Anna Maria Coclite was awarded an ERC Starting Grant from the European Community, making her the first woman in TU Graz to be rewarded with the prize.

In an interview for Trending Topics, Dr. Coclite brought more light and insights into her latest research project.

Trending Topics: Dr. Coclite, congratulations on your impressive research on multisensory hybrid materials. What sparked your interest in this less traditional field?

Dr. Anna Maria Coclite: Well, the interest came from the fact that for years we have been studying stimuli-responsive materials or materials that respond to the stimuli of the environment. At some point, I just thought, “Okay, I want to make a sensor out of this” because the response is so fast and large – it doubles and even triples its shape. This could easily be connected to other types of materials that then translate this increased thickness into a measurable quantity. Then the question came of where we need this sensitive and multisensorial information and the skin came to my mind as a good example.

Can you tell us more about the nature of the so-called “artificial skin”?

Basically, the artificial skin is a thin foil on which we have put some of the sensors I told you about. This is why it is called artificial – there is nothing biological about it. There are electrical transmitters that are triggered by movement in the environment and that way the material reacts simultaneously to force, humidity, and temperature and emits corresponding electronic signals. In addition, it is extremely thin, only 0.006 millimeters. The human epidermis, for instance, is 0.03 to 2 millimeters thick. The “Smartskin” can also register objects, such as micro-organisms, that are too small for human skin.

In what industries could such sensitive material be used? Could it find application in our daily life?

I will be very eager to have it applied to smart prostheses. Prostheses can have tactile information so the patient can move prosthetic hands, for example, lift an object and feel if the object is light or heavy weight and regulate the amount of force needed to grab different objects. Currently, patients are not able to feel if they are grabbing a hot cup or a piece of ice, they won’t be able to distinguish between the two temperatures. And I think that adding artificial skin to the prostheses would easily advance the sensorial information that could be gotten from these materials.

Patients won’t require to have an external chip or anything. The way prostheses work at the moment is that there is a socket that is attached to the hand, let’s say. This socket is also connected to the nerves and with brain waves, the patient could move the prostheses. So there is already a way to create a connection between the brain and the prostheses through electrical stimuli. With artificial skin, we would have to slightly reverse the process so we could send signals and electrical information backward – from the skin to the brain.

I am not saying it is easy. It will require a few more years of research. I think at least another decade.

How expensive and complicated is the production of such sensitive material?

It is actually not that complex because it is based on processes that are already available and in application. For example, when producing integrated circuits. In the semi-conductory industry, these methods are already used and scaled up. Combining them in pilot lines would make the fabrication much cheaper than single batch processes.

There are plenty of STEM startups in Europe. Would you like to see more businesses working on or along science-related projects?

Of course. I think it is a great added value for a startup if they collaborate with or on an idea coming out of the university, that could easily be translated into a commercial product.

We ourselves are looking into the possibility of founding our own startup. (Editorial: We will keep you posted on that!) We would be trying to commercialize exactly the Smartskin as a product.

Talking about commercialization, what do you imagine would be the first product using your material that reaches the popular market?

Probably prostheses. Other areas are also smart watches, touchscreens, robotics, and even helping victims of burns.

You have experience working in a legendary institution such as the MIT. How is “doing science” in Austria different than MIT and has Austria the potential of becoming a world-renown research destination?

I can talk only about my personal experience. It all varies from field to field, from lab to lab. But from my experience, the research at the MIT has the great advantage of having access to open laboratories. So if researchers want to use specific equipment, they could ask for permission, maybe pay a small fee, but still, they are allowed to go to the laboratory and use the equipment they need. And I think this is really great because, especially in more interdisciplinary fields, you cannot have all possible instruments in your laboratory. This will require an immense amount of investment from the university. Having open laboratories, where a lot of equipment is available and every researcher could use it, makes the life of researchers much easier and optimizes the process. This I haven’t found in Graz yet, maybe it is different in Vienna.

But for sure Austria has the potential of contributing a lot to the research in some fields. And the Austrian quality is really looked for.

And at the end, a more philosophical question – artificial intelligence, artificial skin, biofabrication of tissues and organs… How close are we as a society to understanding the human body entirely?

(laughs) I think there is still a lot to be done. The human body is still a very organic device. There are a lot of functions and each of them is connected to the rest in some way. If we refer to artificial skin, all the different functions of the skin are connected in one single organ and we are still not at the point of reproducing all the amazing features of the skin.